Will a tidal wave of decentralised marketplaces disrupt the behemoth?

The sharing economy was one the great inventions of the internet.

A population of marketplaces, that enabled a connection between buyers and sellers of goods or services that was never before possible.

For instance, before Uber came to London, the famous Black Cab service was a taxi riders only option.

For a driver, gaining a Black Cab license is a laborious and expensive process. It involves passing a test, known as ‘The Knowledge’ which takes an average of 34 months to complete, and the acquisition of a specific model of car, the Hackney Carriage.

All one needs to become an Uber Driver is a car, of any variety, a valid UK license and a phone connected to the internet. The sign-up process takes no more than a week.

The average Uber journey in London today costs 40% less than the same journey taken in a Black Cab.

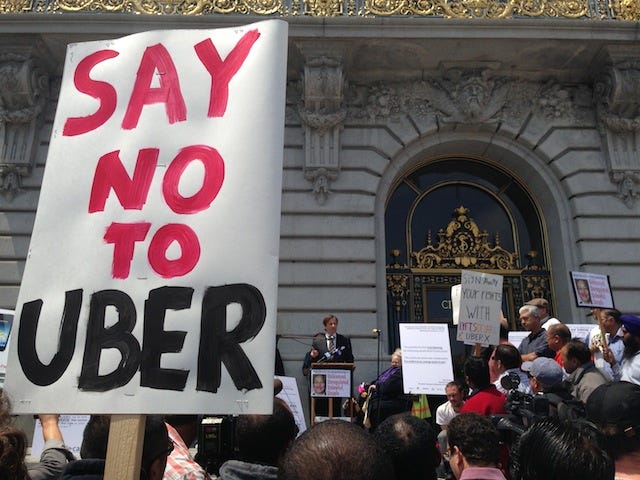

Uber has disrupted taxi hailing services around the world.

The rise of these sharing economy marketplaces has enabled the meeting of supply and demand across a number of previously inefficient markets, from taxi services, to hotel booking and food delivery.

These new age bazars grew in might and reach by leveraging network effects. In doing so they have done a tremendous utility in the world by inputing trust and liquidity into different arenas, allowing unacquainted individuals to transact securely with one another.

When buys or sells something on Amazon Marketplace today, they don’t place their trust in the buyer or the seller. They place their trust in Amazon.

But there are some drawbacks.

The sharing economy is not geographically ubiquitous. These companies don’t operate everywhere. As such, some people are barred from their utility.

Sweden has no access to Amazon.

The entire country of Italy has banned Uber.

In New York, renting a home as a holiday with Airbnb is illegal.

More often than not it is the marginalised and impoverished countries of the world that are barricaded from their utility. Africa has no access to Amazon, Uber or AirBnB.

As technology rises inequality does too.

Secondly, due to the powerful force of network effects at scale, these marketplaces exert a degree a monopoly power over the markets they were built to serve.

With such influence comes the proclivity to extract more value from the buyers and sellers than a conventional market would usually permit.

Jeff Bezos famously said, ‘your margin is my opportunity’

Amazon Marketplace charges 15% for any items sold.

Uber charges 25% to all drivers on each fare.

AirBnB charges up to 20% per booking.

Externalities with these marketplace monopolies emerge in different areas too.

How frequently do you see Uber in the news, with headlines associated with drivers rights and the safety of passengers?

The scale and success of these platforms is a gift and a curse.

Can technology can allow sharing economy to evolve further?

Could the continuing innovation allow us to maintain the utility of the sharing economy, whilst curbing the monopolistic externalities of the companies involved?

Blockchain technology could be seen as a potential answer.

The Ethereum Network, founded in 2013 by Vitalik Buterin pioneered the invention and use of Smart Contracts.

‘A smart contract is a self-executing contract with the terms of the agreement between buyer and seller being directly written into lines of code. The code and the agreements contained therein exist across a distributed, decentralised blockchain network.’

Smart Contracts eliminate the reliance on centralised authorities to infuse trust and liquidity into a marketplace.

In this instance, the trust between the buyer and the seller and the security of the payment can be undertaken by the Smart Contract.

Today we place our trust in marketplaces like Amazon, Uber and AirBnB. Tomorrow we may place our trust in Smart Contracts on the blockchain.

What would a decentralised marketplace, based on Smart Contracts, look like?

Buyers and sellers would be able to extract maximum utility out of each of their transactions. At a large enough scale, they could leverage the network effects inherent in a large internet marketplace, but they wouldn’t need to lose value in transaction fees and commission to an centralised company.

Perhaps each and every one of us would be our own walking e-commerce stores for the individual goods and services that each of us can uniquely offer.

Each of us would have the ability to make secure and and commission-less transactions with unacquainted individuals. We would no longer need an Amazon to find a suitable Buyer or a Paypal to manage the payment process.

On the surface, it seems like a perfectly capitalist utopia.

But human nature many impede technological advancement here.

Human still are hardwired to be tribal by nature, and it is very difficult for us to have real trust for anyone outside the 150 people we have direct relationships with. This scientific truth is known as Dunbar’s Number.

Companies were essentially stories that we tell each other as a function of capitalism to get over the issue of Dunbar’s Number. Instead of trusting in people, we place are trust in companies.

Before the creation of companies, we had no choice but to trade in marketplaces within our immediate circle of 150 people. The creation of companies allowed us expand our horizons beyond 150 people, which in turn catalysed the development of a truly globalised world economy.

I understand and acknowledge the security of Smart Contracts as a transaction medium. The question is will we collectively be able to place our trust in microprograms on the blockchain in the same way that we have learned to put our faith in centralised companies?

Will our human nature allow it?

I am not yet convinced. Time will tell.

If you found the article interesting, please sign-up to my blog on the application of Blockchain Technology to the world of Commerce at: